Bird migration has always fascinated me, but I’ve had questions too about how it happens. How birds find their way down to their winter digs and back again. How birds, like Sandhill Cranes, return to the exact same breeding spot every year. How they often make this voyage in the dark of night.

I’m reading a new book called Flight Paths by Rebecca Heisman. It’s subtitled How a Passionate and Quirky Group of Pioneering Scientists Solved the Mystery of Bird Migration. It’s not the first book written on the topic, but it does have the most recent information tracing the development of each technique used to track bird migration.

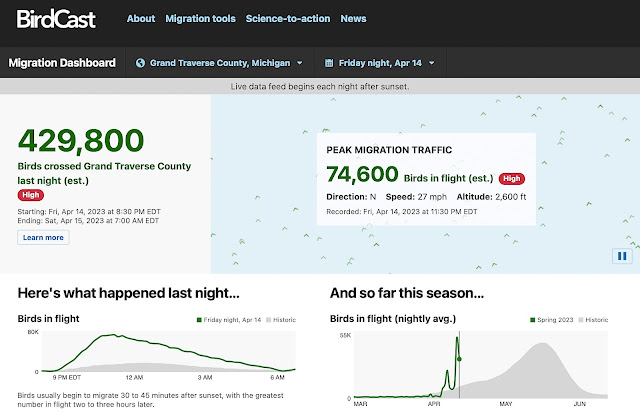

Closer to home, I’ve been following the migratory numbers and they’ve really gone up substantially in the last month. I check daily, but last Saturday, for example, over 429,00 birds passed through Grand Traverse County overnight. The Flight Paths book has a whole chapter on the evolution of Birdcast.

Getting myself outside in farm country, I’ve seen many migrants return. With the ponds completely thawed, Red-winged Blackbirds have taken their regular spots atop cattails and their repeated trills fill the air.

I love woodpeckers and was delighted to see this Northern Flicker had returned from points south. I waited to hear the drumming technique it uses to attract a mate, but it didn’t happen.

I also saw this Tree Swallow keeping toasty on an electrical line. Not surprising since it’s probably been used to warmer climes in Mexico and the Gulf Coast.

I’d not seen this next bird before, a male Brown-headed Cowbird. They are know to be brood parasites, meaning they deposit their eggs in nests belonging to birds of other species.

And, of course, my favorite bird has returned in full force. I’m seeing Sandhill Cranes all over the place, eating dregs in corn fields or hanging out in marshes. Hoping to see some mating dances soon.